|

|

|

| Relativity

in brief... or in detail.. |

Is the speed of light constant? "Varying constants" (Beyond Relativity 2)

About physical measurementWhat can we measure, and how do we measure it? First, physicists can only measure ratios. When we measure an interval of time, we do something like counting the ticks of a clock (or the vibrations of a wave). When we report an interval of 10.5 seconds, we mean that the clock ticked 10 times and was halfway through its next period. (Or that the millisecond oscillator had undergone about 10,500 oscillations, or ...) When we measure length, we could measure the ratio of the measured length to a length marked on our ruler. Often we measure it by measuring an angle, the way surveyors do, which is also the ratio of two lengths.It is only possible to measure a number; one cannot measure units. When you measure a length of 4.7 m, you are measuring the number 4.7. The length is 4.7 times longer than a metre rule. Did the experiments of Michelson and Morley measure the speed of light? What they measured directly was the angle at which maxima and minima appeared in the interference pattern. What they inferred from that was the ratio of time taken by light to travel return trips of the two arms of the spectrometer, and then the various values of the ratio of two values of that ratio, measured when the spectrometer was in different orientations or at different times of the year. One could say that they determined the ratio of the speed(s) of light in the two directions. For example, the conclusion based on the Michelson-Morely experiment is that ratio of the speed of light travelling in the North-South direction to that of light travelling in the East-West direction is one. (The surprising thing is that it is one even when the laboratory is moving in the East-West direction, with respect to the sun, as we saw on in the main site.)

Is the speed of light constant?What would it mean to say that c varied with time? Would it actually mean anything? In conventional units, the metre is defined as the distance that light travels in about 3 nanoseconds. (This is not quite the same thing as saying that the metre is the distance travelled in 1/c seconds.) Suppose that we calibrate marks on a ruler using this definition one year, then next year find that light takes longer than 3 ns to travel the length of the ruler. According to the definition, we wouldn't say that the speed of light had fallen, but that the ruler had lengthened. How could that be? What would that mean?Now the size of the ruler depends upon the size of atoms, which in turn is related (in our units) to quantum mechanical and electrical quantities. Could the atoms in the ruler have grown because electricity had faded, or because Planck's constant had increased? How would we know which?

Time, space, electricity and quantum mechanicsOur imaginary experiment shows that electrical and quantum effects are inter-related. Charge is carried by electrons and protons, which are subject to (quantum) mechanical laws. It is meaningless to talk of changes in an electromagnetic constant or a quantum mechanical one alone. Asking whether the speed of light changes over time superficially appears to be a reasonable question: it makes grammatical sense. But it doesn't make scientific sense. In science, a proposition must be, in principle, testable. (For instance, if you propose that there is an invisible gorilla in the room, and that she has no mass and no effects that can be detected, then your proposition is not a scientific one.)

The fine structure constant, αSo is there something that physicists can measure for which a change over time would have meaning? Yes, there is. Any quantity that doesn't have units can be measured as a ratio. For example, the fine structure constant α is a measure of the relationship between electromagnetic effects and quantum effects and it has no units.Because it has no units, we can think of it as a ratio. Here is a simple explanation: In the Bohr-de Broglie-Sommerfeld model of the hydrogen atom, an electron 'orbits'* a proton, 'travelling' in a circle at 'speed' vH. In this picture, the fine structure constant

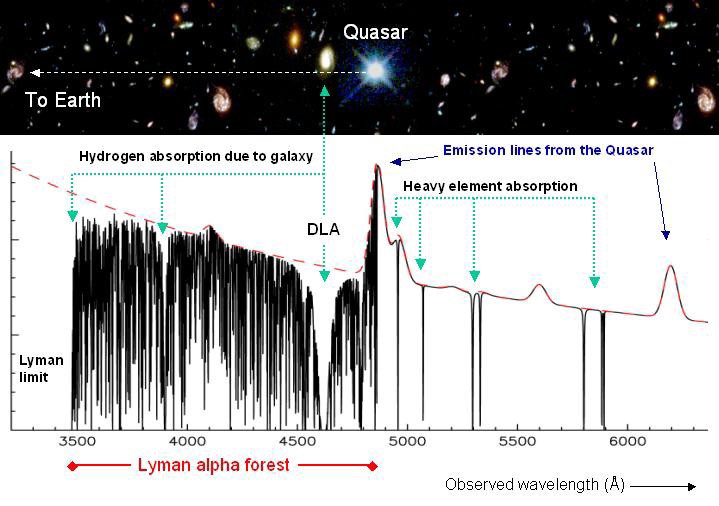

Has the fine structure constant changed over time?The obvious answer is: not much, or we should have noticed it. The temperature of stars (including the sun) is a strong function of α, so even a modest change would have been very observable. For instance, life has been on Earth for at least a quarter of the age of the universe, and perhaps as much as a third. This puts a limit on how much the sun's temperature could have varied over that time. (Another, much stricter limit is imposed by measurements of the reaction products of a natural atomic reactor at Oklo in Gabon that was active about two billion years ago.) So any change over this time scale must be small. But is the change exactly zero over all time?Several years ago, my colleagues at UNSW, cosmologist John Webb and theoretical physicists Victor Flambaum and Vladimir Dzuba developed a new way of determining α from the spectra of quasar light that had passed through gas clouds on its way to earth. Quasars are very bright, so one can measure the atomic absorption spectra of very distant gas clouds. (Image courtesy John Webb.)  Because c is finite, "distant" means "long ago". So John and Victor thought that their new, very sensitive test would be a way of putting a new, very tight limit on the possible change in α over times comparable with the age of the universe. An interesting problem for a good graduate student, and so Michael Murphy joined them in the search. Michelson and Morley expected a small, finite result and found zero. Murphy, Flambaum and Webb expected zero and found a very small, but statistically significant effect. These researchers hasten to add that the effect is small, is observed only in the very young universe (and is therefore not in disagreement with other determinations of α in more recent times). They also stress that the results are so unexpected that they really call for a replication by other, independent researchers using independent data from the same era. Nevertheless, their work is a tantalising hint that the laws of Nature might change on cosmological time scales or distances.

What would α(t) tell us about c?Well, let's write a few different expressions for α and see. In these expressions, e is the magnitude of the charge on the electron, kelec is Coulomb's constant for electricity, ε0 and μ0 are the electric permittivity and the magnetic permeability of the vacuum. For the moment, let's consider only units in the SI. There are a few ways of making sets of units for physical measurements that are considerably more logical than those that we use today. However, don't expect them to be introduced into everyday life, because the unit of speed, c, is impractically large. ("Well, driver, I clocked you at 120 nanocees, about 1046 plancks ago.") Notice that, in the natural system of units, once you have determined electric and magnetic effects, the speed of light in vacuum is exactly one (unit of speed). What is the value Plank's constant, h, in a natural system of units? If we chose the unit of the electric charge to be that on the proton, then it would have the value 68.5. More common in the use of natural units, however, is to set Planck's constant as the unit of action, and then α determines the unit of charge. Let's return to our questions above that concern the relations among atom sizes, vibration frequencies and electromagnetism. In the (most common) natural system of units, we cannot ask whether Planck's constant varied, because it is one. After a little reflection, all versions of these questions (providing they don't involve gravity) convert to asking whether α varied. α is a purely numerical ratio that has a meaning in all systems of units, including natural ones. So it is a meaningful question to ask whether α changes. The answer is not definitively known yet. If α has changed, what would this mean for relativity? As far as I can see, it has no immediate consequences — it doesn't pose any obvious threat to Special Relativity. Like Galileo's relativity, Special Relativity is a theory of relative motion. However, you can imagine the temptation for a sub-editor on the science page to write a headline such as "speed of light not constant" or "Einstein wrong". So, no matter how careful the scientists have been in their press release, you may find some peculiar statements in the non-specialist publications. Update: Variations of α in spaceSince I wrote this page, Webb's team have calculated α for very distant sources in different directions in the sky. They report a variation of α with direction: a dipole in the sky, slightly greater than the terrestrial value in one direction, slightly smaller in the opposite. Again, the variations are extremely small and the results are considered tentative by many. But let's pursue this idea and consider that many cosmologists think that the Universe is very much larger than the part that is visible to us (the part from which light can reach us in a time less than the age of the Universe). Suppose then that the laws of physics (including but not limited to α) vary substantially over the Universe. This gives an interesting perspective on a question asked by many physicists and philosophers: The Goldilocks question. Why is the Universe just right for us? I particularly like how Martin Rees addresses this question in his book: Just Six Numbers: The Deep Forces that Shape the Universe. We need a large, expanding universe with long-lived stars. We need stable (but not too stable) elements ... if the values of the important dimensionless ratios (including α) were different by even modest amounts, human life would be impossible. So why is the Universe just right for us? Spatial variation in ratios is one neat answer. If only a small range of α allows life, then it is no surprise that we find ourselves in the region of the Universe where α lies in that range. (Another possible answer considers multiple universes (which are produced in huge numbers by some cosmologies). If these universes have different physical laws, then it shouldn't be a surprise that we find ourselves in a universe with laws that allow our existence.) ReferencesA popular account of the possible variation in α is given by J. Webb (2003) "Are the laws of nature changing with time?" in Physics World, April, 33-38. Another popular account is "Inconstant Constants", by John K Webb and John D Barrow in Scientific American, June 2005. For quite serious technical accounts, about the results and the method, see

* I referred above to an electron 'orbiting' a proton in the Bohr-de Broglie-Sommerfeld model of the hydrogen atom. Although this is a convenient way to introduce α, it is misleading. 'Orbit' suggests a well defined path, so that position at any time is known. Because an atom has a size of about 0.1 nanometres, to talk of an orbit on this scale would suggest that the position of the election could have a meaning on a smaller scale than this (say we know where it is with a precision of 0.01 nm). This is not the case. In general, a small thing like electrons does not have defined paths and its position at a given time cannot be defined precisely, because of the Uncertainty Principle. So it is misleading to talk about the electron 'orbiting' the proton, and I apologise for having misled you. Hence the scare quotes on that paragraph. However, quantum mechanics is quite another story.

|

Home

| Summary

| Quiz

|

Credits

|

|